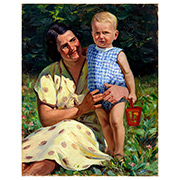

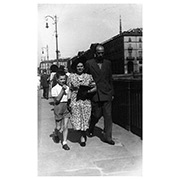

Michelangelo Pistoletto was born in Biella (Italy) on June 25, 1933, the only child of Ettore Olivero Pistoletto (1898-1981) and Livia Fila (1896-1971). His father, a painter, originally from Gravere in the Val di Susa, moved to Turin in the twenties with the aim of perfecting his technique. During a long stay in Biella, where he executed a series of works, including a series of monochrome frescoes known as graffiti on the history of the wool craft for the Ermenegildo Zegna wool mill and luxury fashion house, Ettore Olivero met Livia Fila, marrying her in March 1932. A year after Michelangelo’s birth the family went to live in Turin, where his father continued to paint and opened a studio of restoration. Michelangelo learned the basics of drawing and painting from his father while still a child. On Sunday mornings he would accompany his father on his habitual visit to the Galleria Sabauda, whose exhibits included a collection of icons and altarpieces on a gold ground and medieval wooden sculptures that left a deep impression on his memory and would exercise a significant influence on the art he was to produce in the future.

After a bomb fell on his father’s studio during the air raids of 1943, the family moved to Susa, a safer place but one that was subjected to continual roundups of suspected partisans and in whose square he would occasionally see captured men hanged by the Nazis. Returning to Turin after the war, Michelangelo began to work in his father’s restoration studio at the age of fourteen. Through study and the practice of restoration he gained a solid grounding in the Western tradition of painting, especially that of sacred and Renaissance art.

“My father had gone deaf at the age of eight as a consequence of meningitis; he began to look at the world more than to hear it. [...] In class, it might have been in third grade, he couldn’t hear what the teacher was saying and so he copied a fresco of the Madonna he saw through the window. This is how he began to draw, and from that time on the eye was privileged in our family. He studied restoration in order to make some money, but he always painted [...]. I began to work with him when I was fourteen. The hands-on experience of art history I gained by working moment by moment with old-master paintings, I think, was the best schooling one could get [...]. Hundreds of important paintings from all periods came through our workshop, some with enormous problems that had to be studied in depth before the best way of restoring them could be found.”

(M. Pistoletto, interviewed by Umberto Allemandi, in Bolaffi Arte, no. 57 [Milan 1976]).

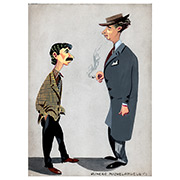

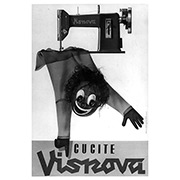

At the age of twenty, on his mother’s advice, he enrolled in a school of commercial art that had just opened in Turin. Its director was Armando Testa, one of the most innovative and celebrated graphic designers in Italy. After about a year Pistoletto became the proprietor of an advertising agency in Turin, which he ran until 1958.

This contact with the world of advertising, at the time very attentive and open to contemporary art, induced him to frequent Turin’s art galleries, which in the fifties offered a very up-to-date selection of international contemporary artistic production.

In April 1953, for instance, he saw for the first time one of Lucio Fontana’s works, a Spatial Concept from the series of the artist’s Holes, on display in the window of a fabric store as part of the exhibition “Arte in vetrina”, an event organized annually in Turin in the stores of the city center.

“At the exhibition “Arte in vetrina” I saw my first Fontana, a picture made of holes that caused a scandal [...]. In that canvas filled with holes there was an amazing leap of an incredible violence. At that moment I was studying at a graphic commercial art school directed by Armando Testa and my drawing teacher Raffaele Pontecorvo [also a painter, whose work Pistoletto would occasionally find alongside his own in his first group exhibitions] at the school said in outrage: if at least these holes of Fontana’s were beautiful, but on top of it all they’re ugly.”

(M. Pistoletto, interviewed by Germano Celant, in Pistoletto [Florence: Electa, 1984], 15).

The works of contemporary artists and the debate that they stirred stimulated him to seek, through art, a personal answer to the existential questions he saw expressed in the different artistic currents. Pistoletto was intensely affected by the battle fought between abstract and figurative art, which was polarizing the artistic debate of those years in Turin too, but he saw figurative painting as a direction more in keeping with his education and culture.